Periodontal Disease Progression: An Interplay Between Plaque Accumulation and Host Immune Response

No two human bodies are exactly alike. For those in the medical field, this can create challenges for predicting and treating health issues in a uniform manner.

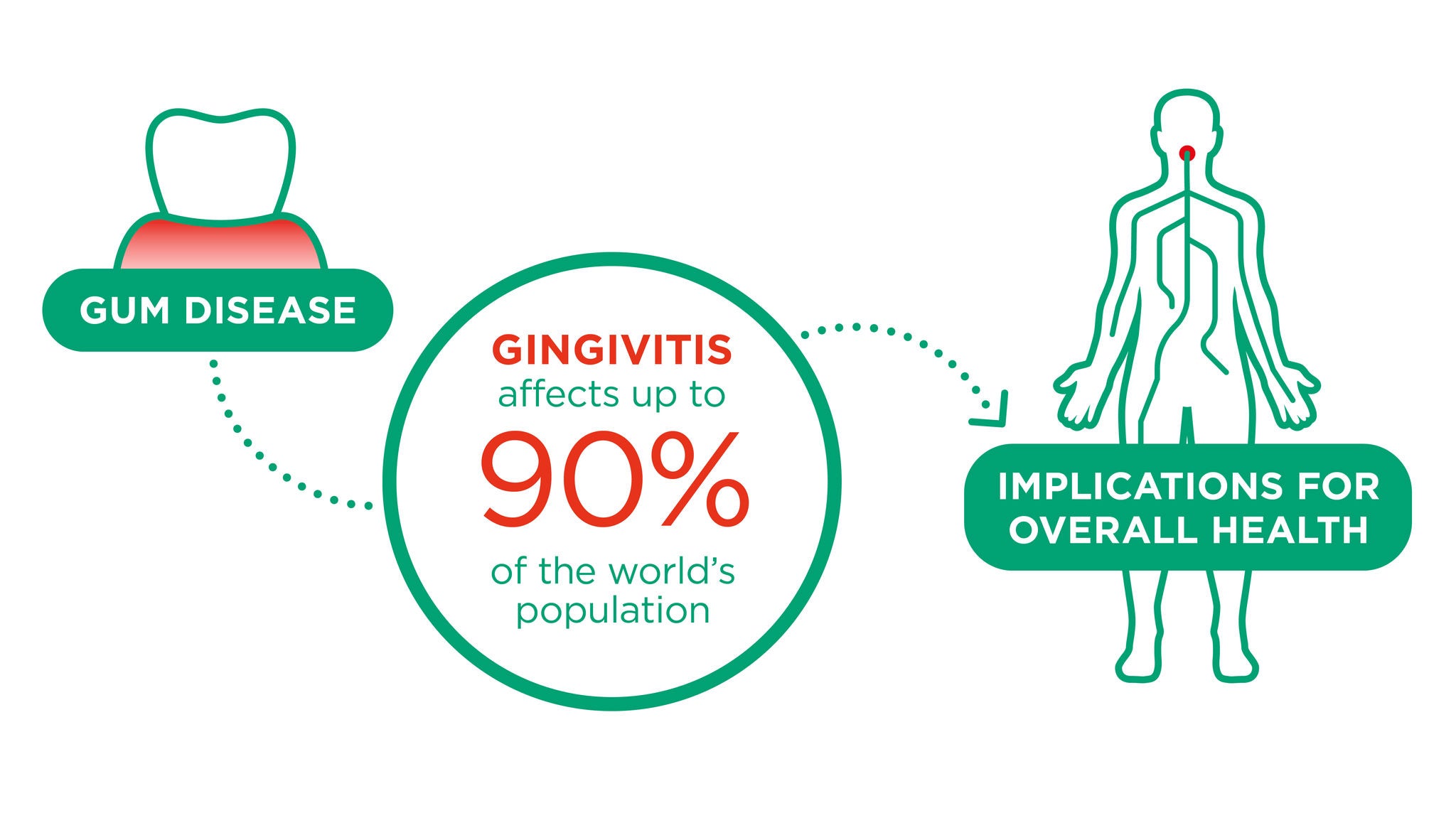

Periodontal disease is a good example. While we can reliably conclude that almost anyone with uncontrolled plaque accumulation will develop an inflammatory response, the subsequent clinical course can vary wildly, from mild gingivitis to much more serious states of periodontitis.

How should dental professionals navigate this uncertainty while providing the best possible guidance and treatment for their patients? Reviewing some of the latest research and analysis around the subject can offer powerful insight.

Let’s take a deeper look at the pathophysiology of periodontal disease, and how to guide patients away from a dreaded “ecological catastrophe” scenario.

Aetiology of periodontitis: a multicausal condition

It is generally understood that there are five discrete causal factors in the aetiology of periodontal disease:

- Genetics

- Lifestyle

- Systemic health

- Oral microbiome (plaque, biofilm)

- Tooth and dentition-related factors

The relative level of contribution for these factors can differ dramatically based on the individual. Plaque accumulation might be a main perpetuator in one patient’s case, whereas an unhealthy lifestyle combined with genetic predisposition might override effective oral care in another’s.

Just as the causal factors can vary, so can the course of development for periodontitis, differing on a per-patient basis and also often tending to follow a nonlinear progression – as is typically the case for chronic inflammatory diseases.

“Nonlinearity in complex systems means that the causes and effects are disproportional so that a small cause may result in a large effect or a large cause may result in a small effect,” explained Loos & van Dyke, 2020, “and that the disease progression rate fluctuates, or rather, can move from one state to another and back.” (In other words, from a homeostatic state to an active one.)

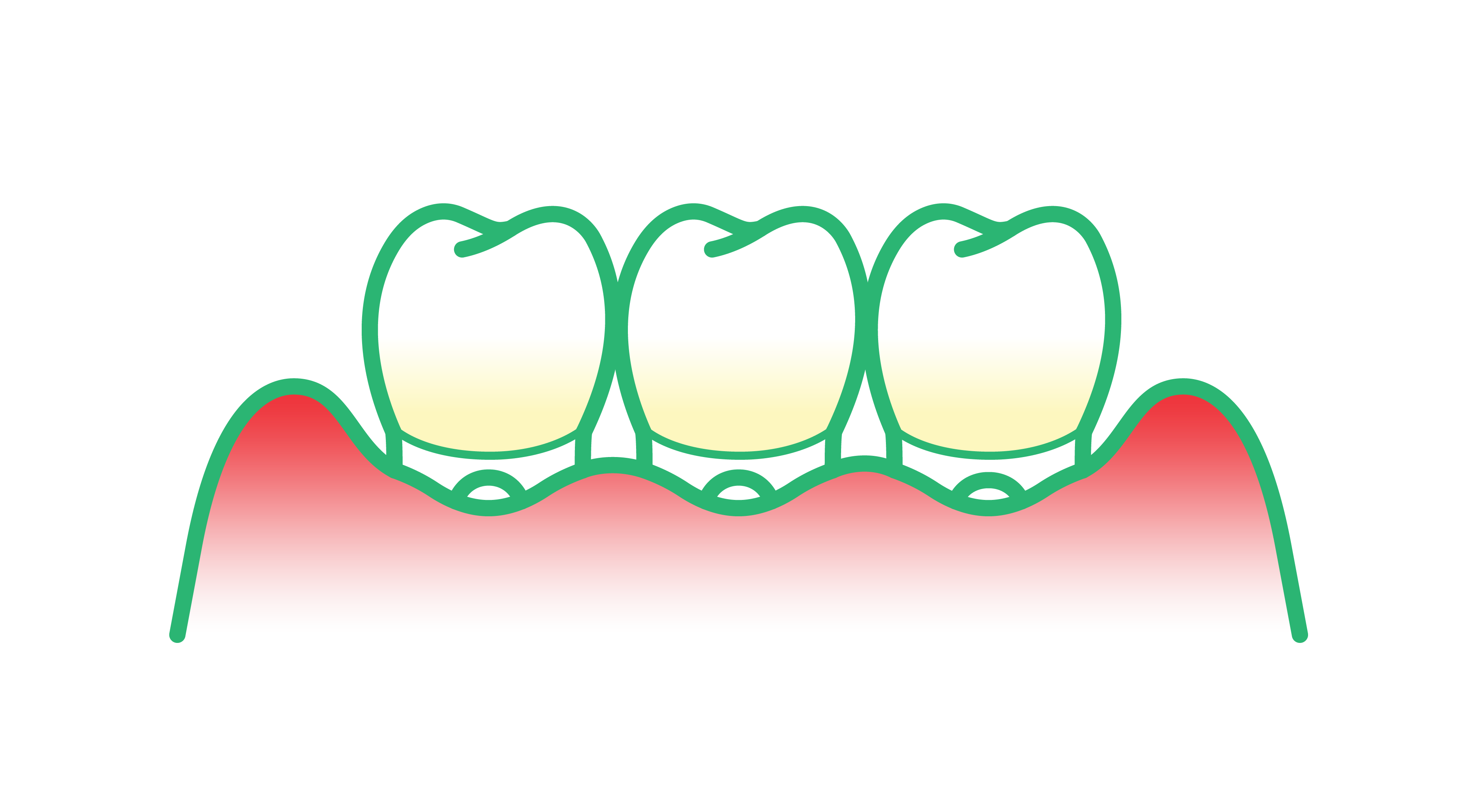

One interesting point of focus for dental professionals is the development of periodontal pockets, and their role in the relationship between host and pathogen.

Periodontal pockets and avoiding the vicious cycle

A review by Murakami et al. in 2018 proposed revisions to the existing classification system for gingival diseases, in order to more strongly underscore the importance of controlling gingival inflammation as a primary defence against periodontitis.

Periodontal pockets, which form via tissue destruction resulting from inflammatory responses to pathogens in plaque, are more susceptible to further plaque accumulation, presenting a risk point that should be evident to any practitioner.

Meanwhile, as studied by Loos & van Dyke, we understand that during the process of plaque accumulation, the host’s immune response and biofilms can shift from symbiosis (healthy microbial balance) to dysbiosis (imbalance). In the latter state, the biofilm becomes more pathogenic and thus induces an even stronger inflammatory response.

In the image below, from Loos & van Dyke’s article, we see what they described as a vicious cycle of “ecological catastrophe” resulting from this interplay.

Needless to say, avoiding such a scenario with patients is paramount. Of course, you can only control what you can control. Host immune response is dependent on genetics and epigenetics, meaning that some groups of people are naturally more susceptible than others.

Genetics cannot be levered as a risk factor, and dentists have limited or no control over other causal factors… with the exception of plaque control. This is where interventional oral care can make a critical impact – steering clear of this “ecological catastrophe” serves as a powerful reinforcing motivator.

Deal with gingivitis through proactive intervention

Accumulation of dental plaque leads to gingival inflammation, which most patients understand. But far fewer are aware of the self-perpetuating disease progression that can take place once the inflammation and potential periodontal pockets develop.

“It should be noted that not all inflammatory sites are destined to progress to periodontitis,” pointed out Murakami et al. “To date, however, no scientific evidence allows us to diagnose which gingivitis sites are susceptible to progression to periodontitis. Thus, to prevent attachment loss and destruction of periodontal tissue, dealing with gingivitis by appropriate local therapeutic intervention is still essential.

“In the future,” they added, “gingival conditions may be diagnosed by objective analytic approaches such as transcriptome characterization and/or categorization of epigenetic changes.”