The Importance Of Behavioral Change And Rituals In Managing Oral Health

How do we encourage patients to improve their daily oral hygiene? Could it be that the secret of creating healthy dental habits lies in a better understanding of behavioral change by oral care professionals?

It’s an everyday scenario for oral health professionals. You give your patients oral hygiene instructions, they listen and agree to improve their brushing and adopt interdental cleaning, then six months later you see them again, with no improvement.

This isn’t because your advice is too difficult to understand or because the patient doesn’t want to change. Rather, it’s because forming and changing habits is a dynamic, slow, and intricate process. To enable this, should we be working together with the patient, rather than trying to force a one-size-fits-all routine?

The statistics on gum disease and dental health are clear

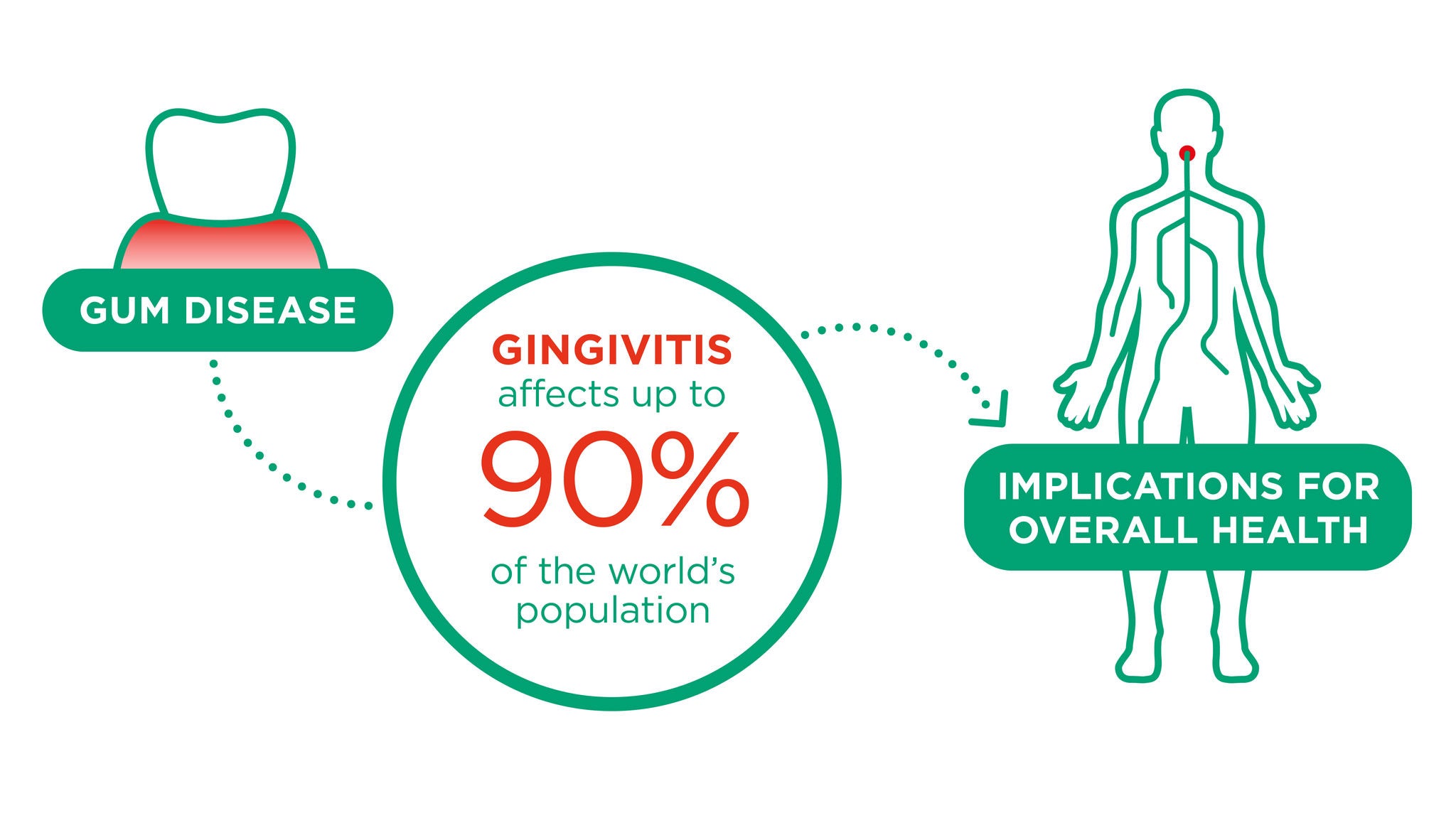

With around 90% of the population experiencing some form of periodontal disease (Pihlstrom et al., 2005), which is a largely preventable disease, it’s clear that there’s much room for improvement.

We’ve produced a white paper that takes an in-depth look at how oral care professionals can help patients improve their oral health using evidence-based behavioral change tactics and strategies. While this article summarizes the key points, you can download the full paper here to find out more.

Good oral care aside, there’s also a significant economic implication: the global economic impact of dental diseases was $442 billion USD in 2010 (Listl et al, 2015). As we all know, most cases of gum disease and cavities are entirely preventable. So, why are they so high?

The link between behavioral change and oral health

When you recommend interdental brushes or new brushing techniques to your patient, you’re asking them to change their behavior. Introducing additional methods of dental care requires additional efforts from both sides, with dentists and dental professionals working out the best approaches to effect lasting change.

The didactic model (“Brush at least twice a day to keep your teeth clean” or “Make sure you clean between your teeth to remove more plaque”) clearly isn’t working, given the high prevalence of periodontal diseases.

Knowledge of tooth decay doesn’t mean compliance in care

All dentists and other dental practitioners give advice to their patients, and its good advice. It’s also very straightforward advice that we assume everyone will understand and follow.

Tooth brushing, using a fluoride toothpaste, combined with interdental cleaning, will help control bacteria and plaque, prevent gum disease and keep your mouth healthy. Interdental brushes and electric toothbrushes provide the best results. Brush at least twice a day, and always clean between your teeth. Add a regular visit to the dentist and/or dental hygienist and that should be that, right? Wrong.

Gum disease is still rife

We rely on human behavior to control plaque. That’s it: that’s the entire strategy. Oral care professionals depend almost solely on their patients’ dental care habits to reduce health risks like tooth decay. This is why it’s crucial that we know how best to deliver these messages, and we can improve this with an understanding of how to change and maintain behavior, reducing the need for treatment.

Our white paper makes the crucial link between behavioral change and dental hygiene, exploring how the use of these strategies is far more effective than simply highlighting the patients' problems and telling them what to do.

The difference between routine and ritual in oral health

One mistake many of us make (and it’s an understandable one) is to think that routines and rituals are the same thing. By focusing on ritual rather than routine, we are better able to facilitate lasting change.

So, what is the difference between routines and rituals? We all have a morning routine, and toothbrushing typically forms part of this. The routine is comprised of things we do to get on with the day. They’re essential, but not what we’d describe as meaningful. They don't require concentration and we do them regularly without thinking. Brushing our teeth, as we describe in our whitepaper, is a typical routine, involving a high level of automation.

What if we add rituals?

These are actions that mean more to us than mechanically going through the motions. We might spend half an hour doing yoga or meditating. We might make a barista-style cappuccino and linger over drinking it. These are the morning rituals; activities that are pleasurable as well as practical, bringing about a sense of holistic wellbeing.

Most of us see cleaning our teeth as a routine and so it’s merely a habit. To encourage excellent oral hygiene, we need to move brushing and interdental cleaning from the routine box into the ritual box. However, reframing this activity from a routine activity to a more holistic ritual is far from easy. How do we enable people to find meaning in brushing their teeth? (And when it’s phrased as bluntly as that, our task feels even more insurmountable!)

The answer lies in understanding how the brain adapts to change. With this information, we’re in a better position to be helpful, and can begin to move our patients’ mindsets from “I have to brush my teeth” to “I want to brush my teeth”.

Understanding behavioral change

Positioning oral hygiene as a ritual can result in meaningful change. Our white paper explores various evidence-based models of behavioral change, which may be effective at changing habits. Here’s a summary of key behavioral frameworks and change models.

The COM-B framework of behavioral change

The COM-B model is a valuable tool, which guides you through how best to approach behavioral change depending on an individual’s mindset and situation. This model incorporates 19 factors of behavioral change and how they interact with each other. At the center are three drivers for change: capability, opportunity, and motivation (hence the name. The “B” stands for behavior).

Where this comes in handy for oral health professionals is that you can start off by identifying which components will work best for each patient.

- Are they capable of understanding the importance of good oral hygiene and physically able to carry it out?

- Do they have the opportunity to clean their teeth well (with positive influencers and financial resources, for example)?

- What motivates them to clean their teeth? Is it a routine rather than ritual?

The model then leads to the next level, intervention strategies, which give you the most appropriate approaches to tackle challenges related to the C, O or M aspects of the model (for example, if you need to address capability, focus on hands-on dental hygiene training). We look at these approaches in more detail in the white paper.

Motivational interviewing

This model is quite known among the dentistry community, although more thorough research is needed into its effectiveness. The premise here is that patients are more likely to change their behavior if that change is truly related to something they value, rather than something imposed on them by someone.

Dental practitioners become counsellors here, as they ask questions from the patient designed to help them reach their own conclusions and buy into healthy dental habits.

The central approaches are collaboration, evocation, and autonomy.

- Firstly, you establish a trusted relationship

- You then ask questions to draw out individual responses

- Then you help your patients form their own conclusions

Change is lasting when we guide it ourselves, and that’s the central principle behind this model.

The planned behavior model

The theory here is that health-related behavior can be predicted by the individual’s intention. In oral hygiene terms, if the patient has a strong intention to improve, say, their interdental brushing to prevent plaque, they probably will according to this model.

There are three factors driving this intention: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. A patient might feel more inclined to take up flossing between their teeth because their partner and kids do it. This is the preferred alternative to: “What’s the point of flossing? Nobody else bothers, and it’s a waste of time.”

How can you use this theory to support your patients?

It can broadly help you to identify which psychosocial characteristics of your patient can be addressed to change their behavior, in a way similar to how the COM-B approach works. However, this model is criticized for overestimating the role of intention, underestimating behavioral complexities, and not really addressing the social and environmental factors.

Goal setting, planning & self-monitoring (GPS)

We can combine elements from these three mainly theoretical models (and others) into a more pragmatic approach: goal setting, planning, and self-monitoring (GPS). This is the approach recommended by the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP), and it draws together evidence-based behavioral change models to create a user-friendly means to facilitate change.

GPS follows a conversational approach, which works well in the typical practitioner and patient relationship. It starts with finding a baseline using assessment questions and discussing common oral health topics. The conversation can naturally lead into areas of discrepancy and need (tooth decay, gum disease, etc), and then into the patient identifying and setting goals that are shared with you, their oral care professional.

The final commitments are made by the patient - and that’s the important part. Patient and professional plan when, where, and how to bring about change, including self-monitoring. Knowledge of the behavior models enables the dentist and hygienist to guide the conversation towards self-selected dental goals.

Healthy teeth and gums are inextricably linked to the overall health of the patient. When your patients feel positive about oral health, it can be seen in their dental care habits.

Understanding behavioral change helps patient care

As dentists and dental professionals, it's important to learn the drivers and barriers of behavioral change for our patients. This enables you to introduce the GPS system, which improves understanding and goal setting.

The patient can then set their own goals based on a greater appreciation of oral health, moving dental hygiene from the routine sphere into the self-care arena of rituals.

For change to be effective, it must be understood, and it must be prioritized. When we take the time to understand the complex drivers of human motivation, we have more meaningful conversations and provide better support.

Download our white paper pack, behavioral strategies to improve oral hygiene

In it, you'll find out more about these behavioral models and the background to this approach.